Bermuda Tax Triangle

Bermuda Tax Triangle

Evolution of the Taxation of Offshore Companies in the EU Perspective for Ukraine

Regarding the Transfer Pricing Directive, its adoption seems more imminent, with many EU countries actively incorporating its standards into their national laws. This tightening of tax erosion countermeasures also impacts cross-border corporate structures in Ukraine. In the post-BEPS landscape, the ‘substance’ of business activities is increasingly crucial. Consequently, countries with lenient tax policies and established tax haven infrastructures are becoming more attractive, as substance requirements necessitate the physical relocation of not just contracts but also personnel.

Cyprus, the Netherlands, Ukraine - a Bermuda Tax Triangle.

As a member of the BEPS club, Ukraine has yet to fully utilise the available tools, remaining a passive participant and suffering unprecedented losses due to unfair taxation practices.

Cyprus is a prime example of a country with a favourable climate and infrastructure, making it an exceptionally popular jurisdiction for Ukrainian businesses.

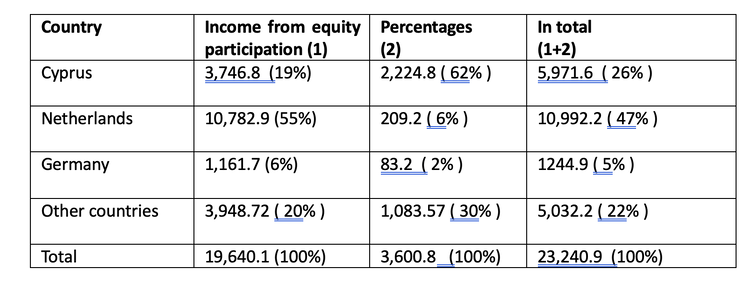

According to the National Bank of Ukraine, over the past five years, Cypriot companies have accrued $5.97 billion in revenue from loans and direct investments in Ukrainian companies. This figure represents 26% of the $23.24 billion paid by Ukrainian companies to non-residents. Notably, Cyprus’s share of interest payments from Ukrainian companies is a staggering 62%, cementing its status as a leading lender and holding a monopoly position in the Ukrainian market.

Income paid to non-residents for 2017-2022, according to the NBU (in billion dollars), shows Cyprus leading in equity participation income and percentages, followed by the Netherlands, Germany, and other countries.

The Netherlands is the second most popular destination, accounting for 47% of total income paid by Ukrainian companies to non-residents from loans and equity participation. The Dutch dominance is evident in capital income, with $10.7 billion, or 55% of all Ukrainian business payments. Thus, 55% of profitable Ukrainian businesses are Dutch-owned, and 62% of solvent Ukrainian loans are Cypriot. Germany’s role in the EU economy does not mirror in investments in Ukraine, suggesting factors other than economic development, like tax convenience, drive investment attractiveness.

The Netherlands and Cyprus are attractive for their tax policies. Dutch law enables tax-neutral structures for dividends, enhancing its role as an investment hub for Ukrainian businesses. Cyprus combines several advantages: a non-domicile regime for taxing residents’ income, a 60-day rule for acquiring tax residency, no tax on securities transactions, a low corporate tax rate, a beneficial double taxation agreement with Ukraine, and a hospitable climate with no language barriers and low entry barriers. Consequently, Cyprus, despite its small size and economy, emerges as a major creditor of Ukrainian business.

These countries can be categorised by their roles in corporate finance, similar to football leagues. Cyprus aligns with regional leagues due to its specific strengths, while the Netherlands plays in top leagues, where teams engage in tax base erosion and profit shifting. The cost of maintaining a corporate presence varies significantly between the two, with the Netherlands starting at 150,000 euros annually, compared to a much lower threshold in Cyprus.”

Can Ukraine Escape the Bermuda Tax Triangle?

Ukraine possesses the tools to move beyond the Bermuda tax triangle, including transfer pricing, the Purpose Test (PPT), and updated double taxation avoidance agreements. However, current tax rates for repatriating income from Ukraine to the Netherlands and Cyprus suggest a different story. With lower rates for interest income, dividends, and royalties, it’s unsurprising that Ukrainian businesses are predominantly owned by Dutch tax-neutral holding structures.

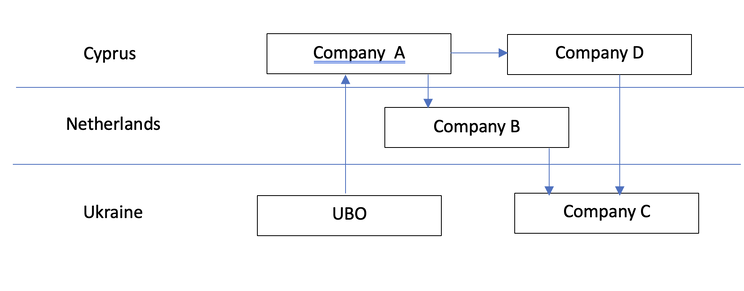

The depicted simplified corporate structure allows all dividends and royalties to be relayed from the only real point of profitability, which is Company C (Ukraine), to the Netherlands at a rate of 5% and then to Cyprus at a rate of 0%. Then, the profits received can be transferred to Company D in the form of capital and issued as loans to the same Company C. The interest on these loans will be taxed by Ukraine at the rate of 2%, and even if all these revenues are then paid to a resident of Ukraine, he will be taxed at the rate of 9%.

It is interesting to compare the tax burden of the given structure and the structure that would be entirely located in Ukraine. Taxes paid by such structures would be comparable or even higher than those paid exclusively in Ukraine. Provided that domestic opportunities are used in terms of tax planning, such as using investment funds in schemes of corporate ownership and reinvestment of profits. But in practice, this does not happen; the choice in favour of a purely Ukrainian corporate structure is unpopular, and there is an explanation for why.

Should taxes also be in Ukraine if the centre of management decisions is in Ukraine?

Ukrainian businesses frequently use Cypriot and Dutch holding companies for several objective reasons. Despite key decisions being made in Ukraine, foreign structures are needed to circumvent Ukraine’s currency regulations, optimise operational taxes and business sales taxes, protect assets from Ukrainian law enforcement, and safeguard against political persecution.

This approach doesn’t prioritise key management decisions, risk management, or establishing profitable activity prerequisites, which one would typically consider first, as in the case of a company like Apple. Revisiting BEPS rules, fully adopted by Ukraine, stipulate that profits should be taxed where they are generated. If tax advantages are a primary reason for an international structure, then it cannot benefit from double taxation avoidance treaties. The main criterion here is the location of key decision-making or the substance. The recommendations state that the essence lies in having adequate and appropriate resources to make key decisions and create activity prerequisites.

An important question arises: How much of the 23 billion dollars paid out to non-residents over the past five years belong to corporations like APPLE, and how much to corporate structures similar to the given example? Applying the Pareto principle, it’s reasonable to assume that 80% of the interest from these 23 billion dollars are paid to non-residents, explicitly created for the aforementioned reasons and not for actual investment purposes. Leading recipient countries in income from Ukrainian businesses seem to validate this. There is nothing inherently wrong or criminal in this, except for one aspect – according to BEPS, these payments should not be subject to the privileges of double taxation avoidance agreements and should be taxed at a rate of 15%.

Despite Ukraine having the means to protect its interests, the country continues to operate within an offshore paradigm. However, the global changes around Ukraine signal the end of this era. ATAD 3 is not unexpected but a deliberate step towards changing the global business environment. The readiness of Ukrainian businesses for such changes and their ability to comply with existing international rules remains an open question. It seems likely, however, that Ukraine will be compelled to follow these rules, potentially surprising businesses accustomed to the old ways.